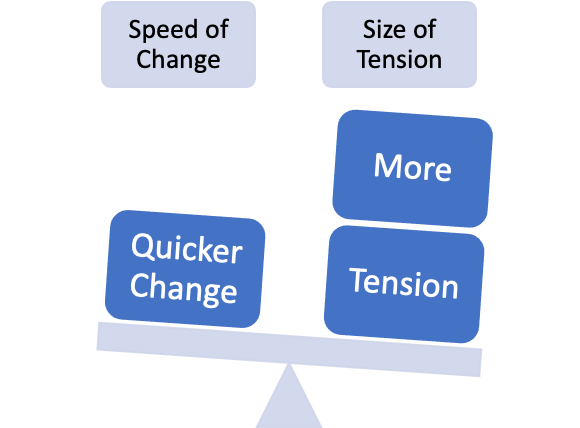

Every organization deals with a certain amount of tension; however, what we often fail to realize is that much of that tension is connected to the speed of change. In other words, the speed of the change equals the size of the tension. The quicker we make changes, the more tension we tend to produce, whereas when we reduce the speed of change, we usually create less tension.

For example, if you introduce a major new vision initiative with little warning, you’re likely going to create tension. People may feel a sense of whiplash as it relates to organizational direction. Or, if you suddenly release a staff member, that unexpected change is going to create tension in the organization (and possibly among other staff members). Again, the speed of change determines the size of tension. Think of it like a seesaw.

When the speed of change is quick, the weight of the tension is heavy. In this scenario, the quick change may not have had much thought put into it (it’s lighter). Or, it may have been thought out thoroughly but executed poorly. Either way, the tension load is heavier, and the leader will end up having to deal with more headaches and heartaches. They’ll have more fallout to clean up and less buy-in from the team and the organization as a whole.

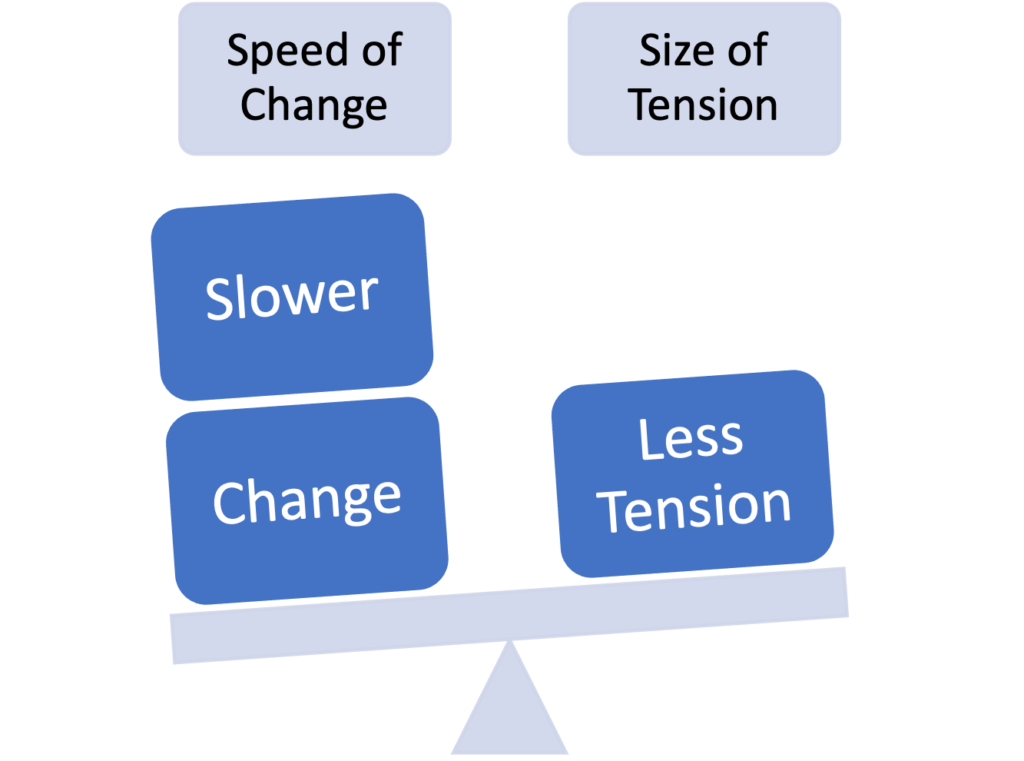

If, on the other hand, the leader slows the speed of change, they will likely have to deal with less organizational tension. In other words, when you increase the length of time to introduce change, it helps the team and organization absorb the possibilities and implications of the change. As a result, unnecessary tension decreases.

While this concept makes sense, most leaders struggle with it at one of two extremes. Both of these extremes can undermine the organization’s progress.

1. Leaders Interpret “Slower Change” as “Slower Progress”

“Slower change” and “slower progress” are two different things. “Slower change” doesn’t mean we drag our feet on pursuing vision or game-changing opportunities. “Slower change” doesn’t mean we become irrelevant and outdated with methods and strategies that no longer work. Instead, “slower change” is all about the pace of communication and execution.

“Slower change” takes a bit more time to plan its execution effectively, and then communicate our strategy clearly. When this happens, buy-in increases. There’s less tension to deal with, and therefore, the impact and outcome of the solution is usually greater (and in the end, faster because there’s less mess to clean up).

The truth is, “quick change” can actually slow your progress because you didn’t take the time to raise the anchor of resistance. That anchor can only be raised when you carefully plan the change (often with input from key leaders), and then thoughtfully communicate the “why” and “how” of the change throughout each layer of the organization. In the end, your change has buy-in which leads to breakthrough.

2. Leaders Assume the Goal is “No Tension”

At the other extreme are leaders who tend to be less welcoming of change. Sometimes they’ve gotten comfortable, are less agile and flexible, or simply accept the idea of change at a slower rate. The struggle these leaders have is thinking the goal of change is “no tension.”

But if you’re a leader, there’s really no such thing as “no tension.” A leader leads the organization to a better future, which implies change, and there’s no such thing as tensionless change. Just ask your body when you start exercising. It will feel the tension, and your sore muscles will let you know it. Sure, you won’t run a 26.2 mile marathon the first time you exercise, but without a sense of urgency, you won’t make any changes either.

Again, the goal isn’t to eliminate tension. In fact, if your goal is to wait until all tension is eliminated, your organization will inherit a greater tension: decline and eventual death. Avoiding all tension only leads to greater problems.

So, what is the goal? The goal is to make necessary change while reducing unnecessary tension. You can’t entirely avoid tension (nor do you want to). But you can reduce tension that is simply unnecessary. One way to do that is to ensure the change is made at the proper speed. And by proper speed, I’m not necessarily talking about months or years.

Again, the proper speed of change is almost always connected to your pace of communication and execution. Therefore, consider the following:

- The bigger the change, the longer the runway needed to get the change airborne.

- Don’t assume everybody knows the “why” and the “how” of the change. You may need to put as much thought into how you communicate the change as you do into how you execute it.

- When communicate change, define the problem, present the solution, and show people how they can be part of the solution.

- Execution almost always requires more time, more people, and more money. Consider what support people will need to execute the change when their plates are already full.

- Seek input from key leaders when assembling your communication and execution strategy. They will help you see your blind spots and lead change with greater effectiveness.

Again, the larger the change, he longer the runway. Smaller and mid-size changes require less runway. In fact, many changes can happen with some thoughtful planning and a handful of conversations with the right people. Don’t overcomplicate it, but always remember, the speed of the change equals the size of the tension.